The native bear

An equilibrium based on exchange and alliance

The bear is a god and, at the same time, ancestor, brother, son and friend for many of the circumboreal cultures which for thousands of years have lived by hunting and breeding.

Examples are the Sami, the Ainu of Japan, the majority of Siberian peoples such as the Nivkh and Ket and native American peoples including the Cree, Beaver and Ojibwa. But numerous ethnic groups have, in fact, been associated with bears in their real or symbolic life. As is often the case in oral cultures, a great many variations of bear-related tales, myths and legends exist, but similar beliefs are found among all these peoples.

A recurring traditional tale tells of a girl, sometimes described as ill-mannered, who lingers in the forest to pick berries. When she inadvertently steps on bear droppings, she curses, breaking the rules of respect for the forest and the animal itself. She is then approached by a handsome young man dressed in a bearskin. The two spend the summer and autumn together, feeding on the food offered by nature, then when winter comes, they find a home in a cave. It is only during the long winter months that the maiden becomes aware of her companion’s true identity. Then in February, children are born from their union.

But there are also stories of young boys and girls being abducted by bears under the eyes of their mother, or of orphans taken under the protection of a bear. It can be a male bear, but more often the children are taken care of by a female, sometimes in human form, with her cubs. These tales have a seemingly predictable ending. The bears are hunted and killed and the humans are reunited with their original family. But there is a twist. Bears have magical powers and are never caught off guard, because they can read men’s intentions. Before allowing itself to be killed, the bear reveals to the abductee or their companions the ritual actions they must perform as a sign of respect for the gift they have received (its death) and forms an alliance with them, giving them powers and skills to become great hunters.

Lithograph of the “Dance of the Bear” from a 1835 painting by George Catlin. In many native North American peoples, people wearing bear masks would perform propitiatory dances, imitating the gait of the animal they were about to hunt.

Bears and other wild animals are considered both physically and magically superior to humans, but there is a relationship of affection and intimacy between them

These stories reveal a vision of man’s role in Nature very different from the Western tradition, associated with the Judaic-Christian culture or Cartesian thought. In these cultures, man is not at the centre of the world and nature was not created for his use. For the Ojibway and Cree, for example, the term “person” does not just identify an individual of the human species. A stone, a fern, a bear or any other animal is also a “person”. All animate and inanimate beings contain a vital part and are endowed with self-awareness and the ability to understand and they are thus able to communicate with each other. Man and nature meet on a plane much closer to the human condition, because they experience the same emotions. In the totemic culture of the Ojibwa, for example, it is the animals that created the world. Animals are considered essentially “human” or rather, an “other” similar to humans and belonging “to the same family”. Even today, every family or clan boasts of their animal progenitors, or of having been born from a union between men and animals. But animals are also closely related to the spirit people who protect them (the spirits of the forest or game).

“Painting of bear, bird and fish” by the Canadian painter Norval Morisseau (1932-2007). Like many of his other works, the painting highlights the connections between different species, emphasising the interdependence of the various elements of nature.

So communication with man is not direct, but takes place through prayers, songs, dreams and rituals. For the Cree peoples, spirits live in “celestial” villages in a world parallel to that of humans. They can change their appearance and send wild animals, such as bears, among humans as messengers. For these peoples, there is a wild “society” that “functions” in much the same way as human society, although more idealised. When killed, the animals must return to the place where they originated. For some cultures, the forest is considered an “other” world, different, terrible and fascinating at the same time. For others, it is a spiritual and regenerative environment that requires purification before entering. For everyone, it is a place of magical encounters. Entering the forest is an epic, spiritual, magical experience that must be done with respect. Man is aware that nature can be benevolent and an ally, but also dangerous or malevolent. Relationships with nature can change in unpredictable ways and their direction is determined by man’s behaviour. To live in harmony with nature requires rules and morals, but above all respect. Each being, each “person”, is linked to the other by subtle connections and these can only be broken by a selfish act against nature, attracting the ill will and vengeance of the spirits.

Twisted branches of ancient beech trees at dusk. The forest is a recurring element in beliefs and literature as a topos in which magic and the supernatural are manifested.

In the hunt, it is the bear that offers himself, but asks to be treated as a “guest” so that his spirit may return among the spirits, thus guaranteeing that other bears are sent among men.

Relationships between men and bears are mostly benign, almost loving, even seductive. This is what emerges from the ceremonies and rituals associated with bear hunting. Many different ethnic groups have hunting rituals and there are great many variations on similar themes. Bears are hunted in autumn when they are fat, in late winter when they are flushed out of their dens, or if they have repeatedly killed livestock. The hunt is lived as a spiritual or magical event and is never accidental, because it is the bear that offers itself. It therefore calls for singing, prayers, rituals, offerings and great festivities. The ceremony appeases the revenge of the spirits, brings good luck in the hunt and prevents diseases, or bear attacks on the flocks. The ritual begins before the hunt and continues through the act of killing until the return to the camp or village. Arrival of the bear’s body is a celebration for everyone. After death, the bear is given hospitality, welcomed into the human social system, dismembered and distributed as food to all members of the camp or village. The bones are then reassembled and hung in the forest to ensure that the bear’s spirit returns to its place of origin, the village of bears. In Siberian shamanic culture, bones have the power to regenerate and recreate the living body. The bear is treated as a person and people come to the banquet with offerings and gifts (such as rice and bilberries), just as they do for a funeral or wedding. The banquet is shared according to a precise hierarchy defined by the body of the bear itself. The elders have more prestige and so are entitled to the best or most magical parts, such as the head, jaw, and neck. They are followed by the men in the hunting party and married women.

Ceremonial scene associated with bear hunting taken from the volume “Ezo Shima Kikan” (Unusual Views of the Island of Ezo [Hokkaido]) by Hata Awagimaro (1799), considered the most important work depicting contemporary Ainu life.

For the peoples of Siberia, taking care of a bear cub is a propitiatory rite to show the spirits that humans are good, thus guaranteeing protection.

Among the Ainu of Japan and the peoples of Eastern Siberia, bears are hunted in dens in late winter to capture the cubs. The cubs born during the winter are brought to the village, welcomed and lovingly raised. Nursing women take care of the cubs and suckle them as if they were their own infants. After a year, at the end of the following winter, the cubs are killed in a well-defined ceremony aimed at sending their spirits to the mountains to find their people who live in a dimension parallel to that of humans. During the ceremony, the bear receives gifts and offerings (millet cakes, cordials and berries). The bear will take the gifts it has received to the spirits and tell them it has been treated well and this will make sure that other bears will be invited to provide food for the village. Among the Ket peoples of the Yenissey in central Siberia, a proper bedroom is prepared for the cubs which are adorned with copper bracelets and earrings. After three years, they are released into the taiga, but as they are recognisable, they are no longer killed, because their role is to carry the message of man’s goodness.

The bear is central to the culture of these peoples, because it embodies the man/animal metaphor better than any other animal and is one of the most magical, or rather, among those with the most powers.

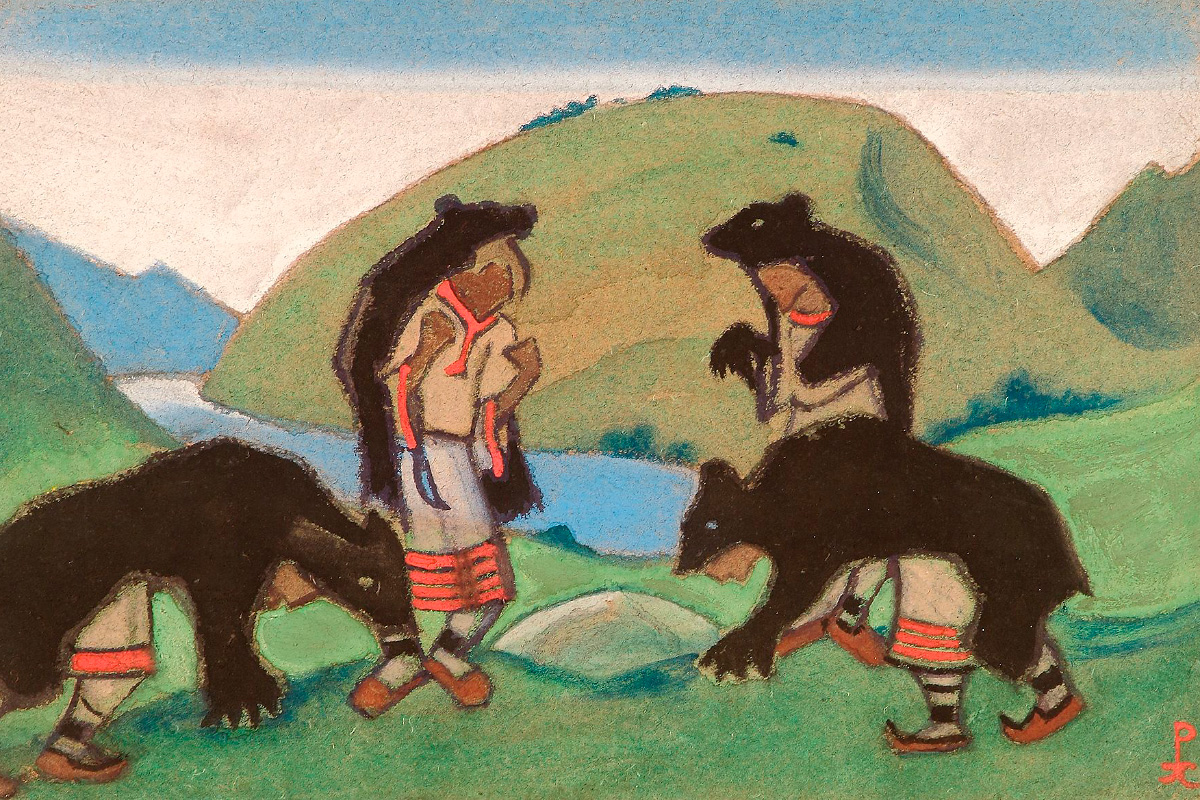

“Ancestors wearing bearskins” by Russian painter Nicholas Roerich, 1944. The portrayal seems to echo the ancient shamanic tradition of the peoples of northern Asia.

Ethnographic information and accounts indicate that the bear was, and is, considered to be endowed with human characteristics for a number of reasons. The structure of its paws is similar to that of our hands and its erect posture resembles our own. Then once skinned, the anatomical features of the bear are very like those of a human, in particular a woman. Bears and men follow the same paths, they are intelligent and cunning. Female bears are loving to their offspring. The bear thus plays a totemic role in many cultures, in other words, it is considered as an ancestor or relative. Among native peoples, each member of the clan has his or her own totemic animal and, not surprisingly, bears are the guide animals of shamans, herbalists and guardians of law and order. The bear is believed to have the power of a shaman. It can predict the future, engage in magical fights, sing, transform itself, disappear and also reveal magical formulas and medicinal ingredients. Its power is at its maximum in the den, when the bear is in a state of apparent death, between sleep and wakefulness. Endowed with supernatural hearing, while in their den, bears are thought to be able to hear all men’s thoughts and ascertain the truthfulness of their oaths. It is therefore best to avoid pronouncing the bear’s name, instead using circumlocutions such as “the angry one”, “short tail”, “lord of the forest”, “honey paw”, “father”, “grandfather”, “old uncle of the woods” and “honey eater”.

The bear comes back to life after hibernation, it is regenerated from the bones hanging in the trees and is considered immortal and a healer. Every part of its body is medicine for men. As they are “sacred”, bears and the forest are also considered pure and innocent. Finnish peoples believed that a normal bear was always innocent and incapable of hurting people. A bear that attacked or killed cattle or people must have been “bewitched”.

As they disappear in winter and reappear in spring, the bear marks the seasons and is the “door” to enter the world of spirits beyond the sky.

“And we are not afraid”, Nicholas Roerich, 1922. Although the scene depicted is contemporary, it seems hinting to the ancient belief that bears are responsible of the passing of seasons.

In many cultures, the bear symbolises the cycle of time, the passing of the seasons and the death and rebirth of nature. All the peoples in the circumboreal zone have always had a deep knowledge of the constellations, using them to keep track of the passage of time. In a legend among the Miꞌkmaq people, a female bear comes out of her long winter sleep in search of food. The first animal to spot her is a titmouse, who during the summer and into the autumn enlists six other birds to kill her, freeing her vital spirit which will sleep lying alongside another bear. Ethnologists have discovered that all the elements of this legend have a stellar correspondence and follow the rotation of the stars in the Ursa Major in the sky from spring until autumn. According to the Oji-Cree, the constellation of the Pleiades was also known as “the bear’s head” and its position in the sky at the zenith indicated that spring had arrived (coinciding with awakening of the bears from hibernation). This is also commemorated in Italy in the alpine festival of Candlemas. But the Pleiades were also believed to be a hole in the sky, a door communicating with the empyrean heaven, with the bear as mediator.

The constellation of Ursa Major above the silhouette of a centuries-old beech tree in the Central Apennines. The evocative power of these seven stars has ancient roots and recurs in different peoples and cultures.

For many peoples living by hunting and animal husbandry, the bear has always been considered an ally and worthy of respect. Breaking a bond with the bear is considered a selfish act against the entire community.

Men who offend bears and nature are destined to become spectral bears and victims of suffering and disease, bringing with them misfortune and woe.