There where the wild things are

The thin line between human and nonhuman animals

Where do “wild things” begin or end? Unlike the imaginary island in Maurice Sendak’s famous children’s book, there is no universal answer. It is a changing concept, influenced by culture, upbringing, environment, what we watch on our screens and our own experience.

For some experts, this is something of a paradox, given that we ourselves are natural beings, in other words, we have co-evolved with all other natural creatures and forces for millions of years and share the same biological functions with the former. But the question is far from trivial, because it is precisely where humans and wild animals overlap that conflicts can occur. The human-fauna interface is seldom static and the greater the risk of encounter or the contact surface, the greater the likelihood of interactions occurring and becoming problematic. The global change taking place on Earth, now in the Anthropocene era, is influenced by many factors able to induce ecosystem alterations at general level, such as climate change, and at local level, with the spread of built-up areas at the expense of natural habitats, or, vice versa, the expansion of wildlife into urban areas. These aspects may also influence each other to an extent that cannot always be foreseen. There are, unfortunately, no quick and decisive solutions and a failure to take the socio-political and biological complexity behind these phenomena into account can only exacerbate tempers, polarise positions and make conflicts irresolvable.

Today, more and more people are afraid of nature, a phenomenon known as biophobia, perhaps one of the biggest obstacles to conservation policies for the animal species considered “most dangerous”.

Is it natural to be afraid of animals like bears and wolves? From an evolutionary point of view, fear kept our human and non-human ancestors alive for millions of years. In nature, a certain degree of fear is innate and almost always highly adaptive, as it helps to identify potential risks and deal with them strategically. A threat, or exposure to a frightening stimulus, is invariably followed by a complex of well-choreographed neurochemical responses, prompting animals to stay, flee or change their way of life. Just think for a moment of any event that has frightened you during your life… a quickening of the heartbeat and a rush, as they say, of adrenalin. So being afraid is not always a bad thing. Fear is also common to both humans and wild animals, but in humans it is much more complex. Human beings have, in fact, a natural tendency to respond instinctively, emotionally and affectively when faced with a risk, as well as to foresee and imagine the consequences of a situation or event. Whether we like it or not, we are imaginative beings and, in evolutionary terms, this makes us unique and sometimes fragile.

An empty subway platform in Rome. One of the many places from which we have completely removed any natural component.

All these factors can turn our fears into real phobias, helped by the sensationalism and “exaggerated” narratives offered by the media. Not only that, but we ever more live in an era characterised by what is known as “environmental amnesia” (in other words, a disconnection from nature) caused by our “urban” way of life, and this increasingly makes nature something unfamiliar and different. But breaking the fundamental link between us and all living systems could have disastrous consequences for the well-being of the planet. Biophobia can, in fact, contribute to reducing people’s willingness to coexist with the most dangerous species such as bears and wolves and to fear any kind of experience in nature. And this also has consequences for human health. Many studies have show that spending time in nature, or relating to the natural world in other ways, triggers neuroendocrine responses that make us feel good. On the contrary, especially in young people, alienation from the natural world contributes to the onset of diseases and developmental and behavioural deficits.

Human beings have a natural tendency to focus more on negative information and this magnifies the extent of the risk in their minds.

How do we assess a risk? Experts have shown that human beings have a tendency to be excessively afraid of some things or not afraid enough of others, in other words, to perceive some risks as bigger or smaller, regardless of the scientific evidence. Why? Let’s talk about emotions again. Our perceptions of anything are always subjective and in an evaluation process, the emotional component is always the protagonist, sometimes overturning any reasoning. Experts, however, also say that the absence of emotions (if that were possible) is equally harmful, because it can lead us to make choices that are not instinctive and not always “intelligent”. It’s all about balance. Then there is the fact that, in order to obtain information, you need to enter a jungle of partly contradictory and often polarised social media data. Experts such as David Ropeik, Harvard University professor and author of several books on risk, have identified a number of elements that can add irrationality to our decisions. Let’s take a look at some of them. The less familiar an event, the more it is subject to myths and legends and the more frightening it is. The more an event makes us feel physically vulnerable, the more we fear it. The worse the consequences of a risk in terms of suffering, the more it terrifies us. For example, we are more afraid of events that can kill “suddenly” (such as a terrorist attack) than those that cause the same number of deaths chronically, such as illness or car accidents.

Headlines on the front page in the aftermath of the terrorist attack on 11 September 2001, one of the news items that most shocked the contemporary collective imagination and greatly influenced political and individual choices in the years to follow.

Regardless of the facts, any risk seems greater when we think it might affect us directly, so it doesn’t matter if it affects one person in a million, that person is us. So it’s clear that an incident such as a bear attack can open a real Pandora’s box of emotions and fear, because it fits perfectly into our natural mental short circuits. And in an instant we become the protagonist of Grizzly Man or The Revenant. Furthermore, human beings naturally fall victim to what are called “media bubbles”, in other words, they have a tendency to only seek out or listen to information that reinforces what they or their group believe. So, what do the experts conclude? It is irrational to urge people to take a rational attitude towards a risk, because it assumes that everyone is capable of understanding numbers and always making the most scientific decisions. On the other hand, it is equally irrational to treat or consider those who find it hard to understand risk figures as ignorant. They are just people. So it is always a matter of stepping not only into other people’s shoes, but in practice into our own.

Knowing how to live and knowing the risks is not a catastrophe, but a way of taking them in small doses and making them part of our daily lives.

Does this mean that science and the public can’t dialogue? Both languages are necessary. But it is crucial to understand that narrowing the perception gap between our fears and the facts is not an easy matter, neither for those whose job it is to inform, nor for those who should listen. It means thinking more carefully and rationally and this contrasts with the emotional and instinctive parts that are naturally more powerful. But if both sides are able to understand the mental shortcuts humans adopt to make decisions about anything, it is possible to consider the facts more clearly and thus give our rational side a little more say in the choices we make. All this could make us feel healthier and safer. When faced with a risk, it is not enough for me to feel objectively “safe” or to know what to do, I also need a certain emotional support.

At dusk, a large male bear emerges stealthily from the centuries-old forest. An example of the typical environment and habits of this rare and elusive animal.

If you know bears, you avoid them, just as bears try to avoid humans. Avoiding risks is the first strategy for aware living in nature.

According to experts, there are a few basic things we can ask ourselves to help us make a more informed judgement on whether something bad is likely to happen to us. First of all, in practical terms, for something to be a risk, not only must the event be dangerous, we must also actually be exposed to it. If I’m in a forest in an area where there are bears, there is an objective risk, as it is a place where bears live freely and the bear can be a dangerous animal. But even if something is dangerous, there are other things you need to know: how dangerous is it? For whom is it dangerous? At what level? In what way? How dangerous is the exposure? For what period of time? At what age? How could I be exposed? If I have all these answers, can the risk of something bad happening to me be reduced? In other words, can I take control of my situation? Let’s try to assess the risk of being attacked by a bear. The premise is that basically bears also fear or avoid humans. Various studies using tracking collars show that, in the Apennines as in the rest of Europe or North America, these animals prefer to live in areas as far away as possible from large human settlements and they prefer taking refuge in less accessible areas during the day, especially in areas frequented by people. Bears avoid humans by leading a more nocturnal life and when a close encounter with a human occurs, in almost all cases, they flee the encounter area and remain hidden for days. In Scandinavia in the early 2000s, researchers began an experimental study to prove with objective data in hand that brown bears prefer to avoid direct confrontation with humans. When we say “sacrifice yourself for science” to improve coexistence, it’s not always just a catchphrase! Researchers, PhD and undergraduate students and volunteers approached thirty bears equipped with GPS tracking collars to distances of as little as 50 metres to assess their reaction to the presence of people, collecting 169 close encounters. The bears were visible in only 15% of the cases and showed no aggressive behaviour, while in 80% of the cases the bears moved away even before being sighted. The study shows that Scandinavian bears are not normally aggressive during encounters with humans.

When I reached the ridge after a 600 metre ascent, my only thought was to sit down and catch my breath. A slow but steady wind cooled my face. Sitting down, I began to swing my body left and right to study where I was, when a few metres away, something more than a shadow among the leaves followed my movements. Time to focus: a bear with a collar was sitting watching me. My first thought, always the silliest: “It’s the bear I caught a few weeks ago, will he take revenge?” Basically, I immediately cast myself as one of the characters in the film “The Killer Whale”. Second thought with a long breath: “Calm down, distract him, don’t scare him, speak with a friendly tone and above all don’t run away”. And that’s what I did. I don’t remember the exact words, but I said something and slowly threw one or two pebbles, I think. And it worked, the bear stood on a rock to observe me better, while I made myself smaller and smaller, then with the utmost calm and above all indifference, he left. It felt as though I were no more relevant than that pebble I had thrown. Fear, fascination, emotion. I only remember that over a period of what seemed like hours, I retreated out of sight and walked away quickly, very quickly.

The figures for cases of brown bear attacks are perhaps encouraging, we are talking of about 10 attacks per year across Europe and on average no more than one event per year resulting in the death of the person involved. So, yes, it is a dangerous event, but a rare one. In almost all cases, these were bears that felt threatened by people. So unlike other animals such as felines, the brown bear does not see humans as prey and attacks mainly if it feels it must defend itself. There are, in fact, situations that can put people at greater risk. Almost all the incidents occurred in the case of encounters with females accompanied by cubs and with a strong protective sense towards them; unexpected close encounters with a bear; in the presence of dogs off the lead (which chased the bears and then returned, or were defended by their owner); or bears attracted and conditioned by human food and thus more easily approached and less shy. There are also situations that must absolutely be avoided, such as approaching a female with cubs or a feeding bear (especially if it’s a carcass), or disturbing an individual in a den or approaching a wounded animal. What does all this mean? Shouldn’t I go to the mountains anymore? Not at all, that would be like deciding not to cross a road ever again because there is a risk of being run over. The above information suggests a number of behaviours you can adopt to avoid a close encounter. If you then find yourself face to face with an animal, it is essential to behave in such a way that the bear does not feel threatened, in other words, don’t provoke or frighten it, send it calming signals, if possible distract it and above all leave it an escape route. Attacks are very rare and improbable events, so defence or possible aggressive behaviour on the part of humans is to be avoided. Fighting is always just a last resort.

The first rule, avoid surprising a bear at close range

1) Be vigilant (for example, don’t walk with headphones on);

2) Stay on established trails and avoid leaving the path;

3) Walk in groups if possible;

3) Announce yourself as you walk along the trail (in other words, don’t walk silently);

4) If you have no visibility on a section of trail and you are cycling or running, slow down and preferably walk that section;

5) If you have a dog and can’t leave it at home, always keep it on a leash.

If you meet a bear that sees you from a distance

1) Remain calm and assess the situation;

2) If you are not alone, stay in the group;

3) Back away slowly, speak in a low voice and do not look at the bear: a direct gaze is perceived as a threat;

3) Do not run, a bear is faster than you and you may tempt it to chase you;

4) Do not approach or chase the bear;

5) If your vehicle is nearby, get in as quickly as possible;

6) If there are cubs in the area, move away from them;

7) Do what you can to leave the bear an escape route.

If you encounter a bear that approaches or chases you

1) Stay still and calm;

2) Identify yourself and send reassuring signals (for example, speak in a calm voice and gesture softly);

3) Avert your gaze: a direct gaze is perceived as a threat;

4) If your backpack was on the ground, slowly put it on your shoulders;

5) Distract the bear in another direction by slowly throwing small objects (such as pebbles) if you have them to hand;

6) If it stops, move away slowly.

If a bear attacks

Playing dead can be an option: drop to the ground face down, interlace your fingers behind your neck and spread your legs to make it harder for the bear to turn you over. Remember that reacting may increase the intensity of the attack.

What if I am in a built-up area? The same rules apply, as well as alerting the relevant public safety authorities. What about the Marsican bear? No attacks or injuries have been documented with certainty in the Apennines. Experts also confirm that it is genetically less aggressive as a consequence of its evolutionary history. But even this has consequences, especially on people’s behaviour. In the Apennines, and particularly in areas such as the PNALM, one of the most critical issues today is extreme biophilia and confidence in bears, in other words, people tend to chase and encircle these animals in built-up areas, sometimes just to take a photo or even a selfie, perhaps at a distance of a few metres, confident they are dealing with a “good” bear. The researchers and technical team at the PNALM alone could tell of dozens and dozens of close-range encounters that ended with the bear moving away spontaneously and many cases where it escaped immediately. But there is an “urban” tourism aimed at searching for wild animals, including red deer, among inhabited streets. On a number of occasions, incorrect behaviour has been observed, such as leaving food for the animals to attract them and see them again.

Close-up portrait of a confident fox, in search of food. The presence of animals in peri-urban areas in the Apennines can be a strong attraction for enthusiasts, the curious and photographers

It should be remembered that losing a natural mistrust of wild animals such as bears and others is just as irrational as having too much: another consequence of an “environmental amnesia” that can lead to the opposite extreme, namely considering any animal as tameable. Wild animals are genetically adapted to have high reactive aggression, they may behave “well”, but they are unpredictable. A wild animal might become “tame”, for example in captivity, but it will never be able to fully understand our language, something dogs can do, but as the result of an artificial selection process by man that began over 10,000 years ago. An example is worth a thousand words. Raymond Coppinger was a research biologist who dedicated a lifetime to studying the behaviour of dogs and other animals. He is not an unfamiliar presence in Abruzzo, because it was here that he came to study the sheep dogs guarding the flocks. In 2000, his friend Erich Klinghammer, director of the Indiana Wolf Park, invited him to enter the enclosure of some wolves that had been living in captivity since they were ten days old and had grown up without parents, without seeing the outside world and in contact with humans. They were used to being on a leash and were very tame. When asked by Raymond how to behave, his friend told him to treat them like dogs. Never was a suggestion more wrong. When Coppinger gave one of the females an affectionate tap on the side, Cassi, the female wolf’s name, bared her teeth and attacked him, while the other wolves prepared to do the same. Fortunately, Coppinger was able to save himself. Who among us does not give dogs affectionate pats? The thought of treating a tame wolf like a dog never crossed his mind again. However docile, a wolf will never let itself be tamed. And the same obviously applies to a bear. What are the conclusions? With a few precautions, you needn’t be afraid of being attacked by a bear in the Apennines, but don’t challenge their excessive tolerance and docility. The preservation of this animal depends on it.

We need more accurate, balanced and solution-focused narratives in which people can also engage, perhaps by changing the paradigms.

Although attacks on humans are rare, they often provoke lethal reactions towards the animals considered responsible for the attack, leading to a decrease in public tolerance towards these species and negative repercussions in terms of conservation. In the event of an incident, both humans and large carnivores lose, that’s why reducing these cases remains a priority in order to improve coexistence and ensure public safety and the conservation of large carnivore populations in the long term. But in the case of species such as bears, even if they are protected, it is not easy to establish or re-establish the legitimacy of actions to conserve them. As stated in the guidelines of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), we are speaking of entrenched or identity conflicts, where the animals are seen as a threat to one’s own identity. In this scenario there is little room for dialogue and collaboration. Exaggerated attitudes, hostility, scepticism and sarcasm prevail among the parties.

The removal of animals, in other words, putting them in captivity or even killing them, is seen as the management solution to many problems, especially by the general public. But is this really the case? It may be a solution in the case of an isolated individual who manifests, for example, chronic aggressive behaviour towards humans, even if unprovoked. But if we are talking about bears that attack to defend themselves because they see us as a danger, can we really think of solving the issue by killing off every animal that acts on instinct as part of its natural repertoire? When an animal is removed, a vacancy will be left for another animal. But perhaps, in this case, it is not the bear, but rather the context. Experts also confirm that this practice may carry more risks than benefits. It can alter the structure and social balance in an animal population and instability can increase conflicts with humans, as well as harm the population itself.

A corner of the Apennine beech forest, one of the most natural areas still surviving in our country.

Suppose we remove an adult male bear. If this individual is dominant, his place will be taken by another male bear who will first kill all cubs that are not his. In the case of wolves, destructuring the pack can lead to greater damage to economic activities. If we step outside the biological sphere, once this process starts, what limits do we set ourselves? It should also be considered that removing a species means creating a chain of side effects that can harm the environment and us too. Removing the wolf from a territory means allowing the indiscriminate growth of, for example, red deer, with a risk of increased damage to agricultural activities and biodiversity in general. So isn’t a non-lethal and preventive approach better?

In order to find solutions to conflicts, we must accept that risks cannot be eliminated, but only reduced and tolerated.

As stated in the IUCN guidelines, the coexistence of humans and wildlife can only be achieved through appropriate and informed collaboration between the various actors to identify a mutually acceptable strategy based on four fundamental principles:

– do no harm,

– understand the problems and the context,

– work together by integrating scientific, social and political aspects

– enable pathways that are sustainable for people and fauna.

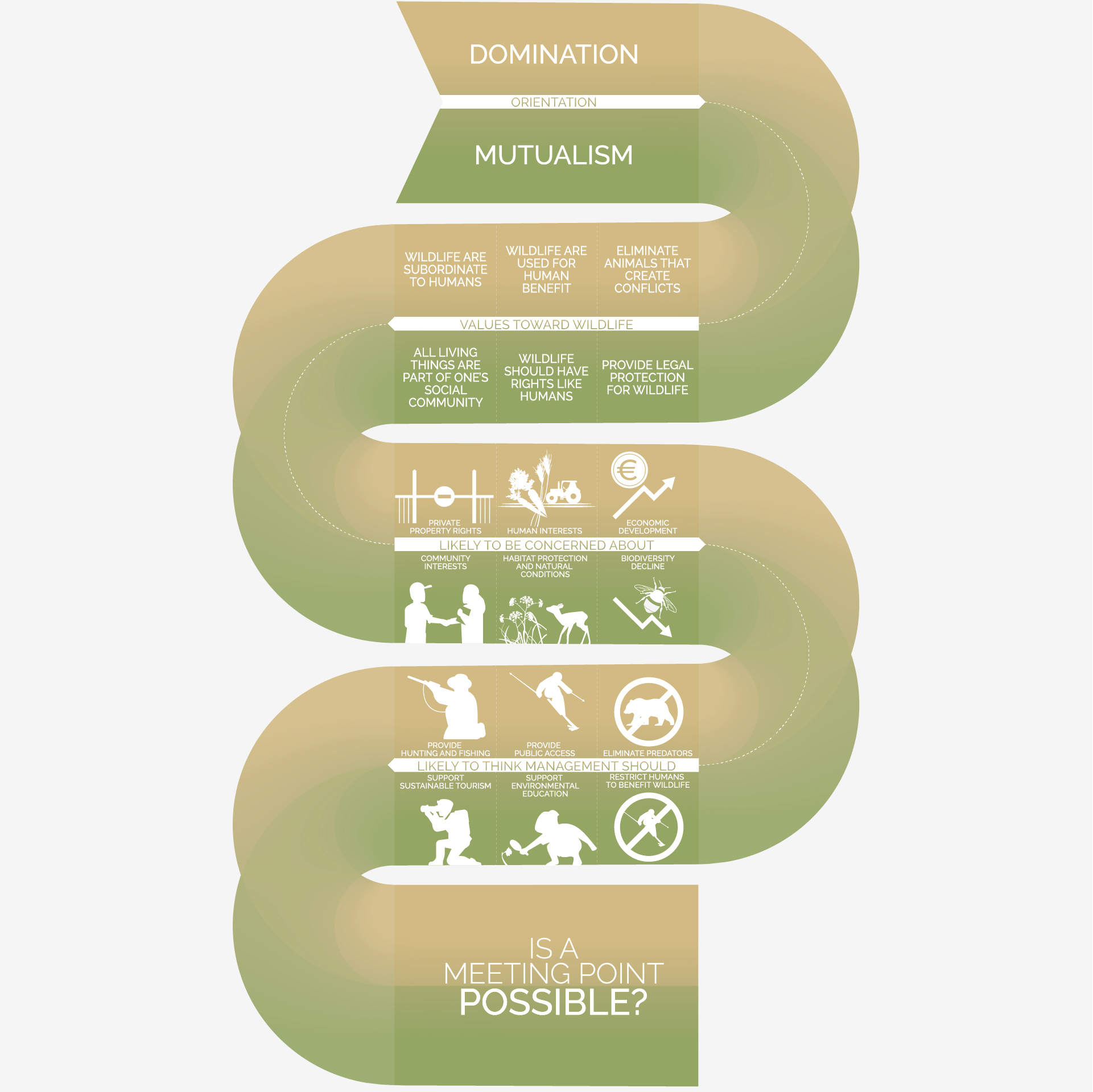

For all this, we perhaps need a paradigm shift, or rather a new vision, and to ask ourselves a question: what if the entirely legitimate difficulties encountered were made even more insuperable by an overly anthropocentric and dominant view of nature? Is it possible to see large carnivores not as difficult or even fearsome bloodthirsty creatures, but as beings trying to survive like us in the same shared environment? Is it possible to move closer to a more mutualistic view of our relationship with nature? A vision, after all, not so new, as it belongs to many other cultures in our world.

Conflicts produce change. When properly addressed, conflicts between humans and wildlife force us to examine the underlying tensions and inequalities and work together to improve the well-being, development and conservation of nature.