The Apennine bear

Stories of adventure, privilege and identity

In the 18th century, the Apennine mountains appeared as a harsh, wild, remote land, made up of impenetrable forests… magnificent, but disquieting to the eyes of a city dweller.

The drove trails and mule and cart tracks providing access to the mountainous parts of Abruzzo and Molise were difficult to follow with the vehicles of the time, such as wagons and carriages, and this would remain true for at least another couple of centuries. Reaching these places was an adventurous experience, not to mention the long, prohibitive winters and the risk of being plundered by brigands or attacked by wild beasts.

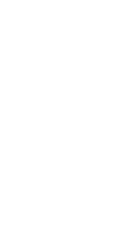

In this historical image, dating back to the early 20th century, one can see numerous pastures and cultivated fields at the foot of the Camosciara Amphitheatre in the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park, now almost completely taken over by nature and covered by dense secondary vegetation. (© Archivio Ente PNALM)

The central Apennines were not uninhabited lands, but instead were home to an agro-pastoral society made up of shepherds and farmers who utilised the mountains for a purely subsistence economy, transforming the steep slopes into fields to grow cereals and pulses, cutting down the woods to create pastures and using the higher meadows to graze animals in the summer. It was also a land of hunters and fishermen. They hunted for sustenance, to obtain meat and furs. The main prey consisted of hares and various species of bird, while otters, stone-martens and wild cats were sought after for their pelt. They also hunted vermin such as wolves, foxes and mustelids to protect their flocks, herds and poultry. It was at this time that the famous “lupari” or wolf-hunters made their appearance, paid to exterminate the predators with rifles, traps and poisoned bait. The practice of killing vermin continued until the 1970s. Lastly, big game species not considered either as vermin or valuable were also hunted for the purposes of recreation, adventure and celebrity. Once red and roe deer had become extinct, chamois and particularly bears were the main game.

This photograph shows the moment when the women say goodbye to the men as they leave with their flocks for the long transhumance to the Tavoliere delle Puglie. (© Archivio Ente PNALM)

Who hunted bears? Bear hunting was the privilege of a few wealthy families with the time and resources necessary to organise the hunts, together with a few particularly experienced and courageous locals who gained fame as “orsari” (bear-hunters). Bears were also sometimes killed by shepherds defending their flocks. According to some testimonies of the time, the bear was considered a placid, almost tameable and shy animal. It avoided man when it could, but was endowed with an extraordinary and brutal strength, especially if wounded, provoked or in defence of its young. The bear was not considered vermin, even though it might “steal” a sheep from the flock now and then. Some sources claim that certain famous inhabitants of the Sangro Valley captured or killed more than thirty bears in their lifetime, some in genuine hand-to-hand combat. So bears were therefore killed in defence of the flocks or as a display of strength and hunting skills.

The historian Luigi Piccioni tells us how the complex and even contradictory relationship with humans and bears evolved from the XVIII centuries up to nowadays.

With the arrival of the national, constitutional monarchy led by King Vittorio Emanuele II, improvements in the road network marked the end of the region’s geographical isolation, accompanied by a change in the history of bears in the Apennines. At the beginning of the last century, under pressure from notables and wealthy families from the Sangro Valley in Abruzzo, an area destined to later become part of the future Abruzzo National Park was designated as a hunting reserve, repeatedly closed and reopened during its troubled history.

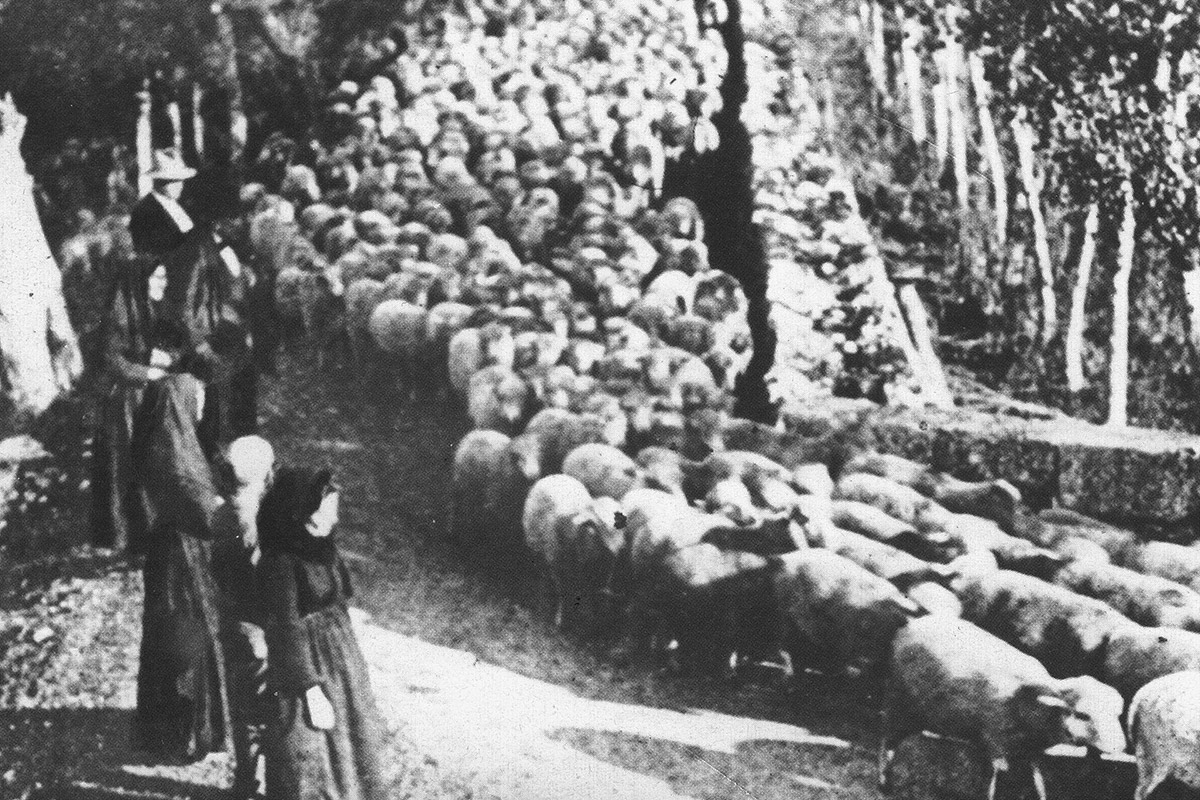

At the end of a hunt, which took place well before the establishment of the National Park and the protection of the species, the heads of two slaughtered bears are surrounded by the trophies of some Apennine chamois in a macabre arrangement. (© Archivio Ente PNALM)

The Apennine mountains were on the 19th century aristocratic hunting circuit and the bear became an act of homage and submission by the most influential local families to enter society and make a political career. Giving a bearskin or bear cub to the nobles or inviting royalty for a hunting party was considered a sign of respect and affiliation to the royal family of Savoy and all that orbited around it and, in fact, gifts to the nobility had been a recurring theme from Roman times through to the medieval nobility. In the Apennines, the bear thus became a symbol not only of adventure, skill and courage, but also of homage and privilege.

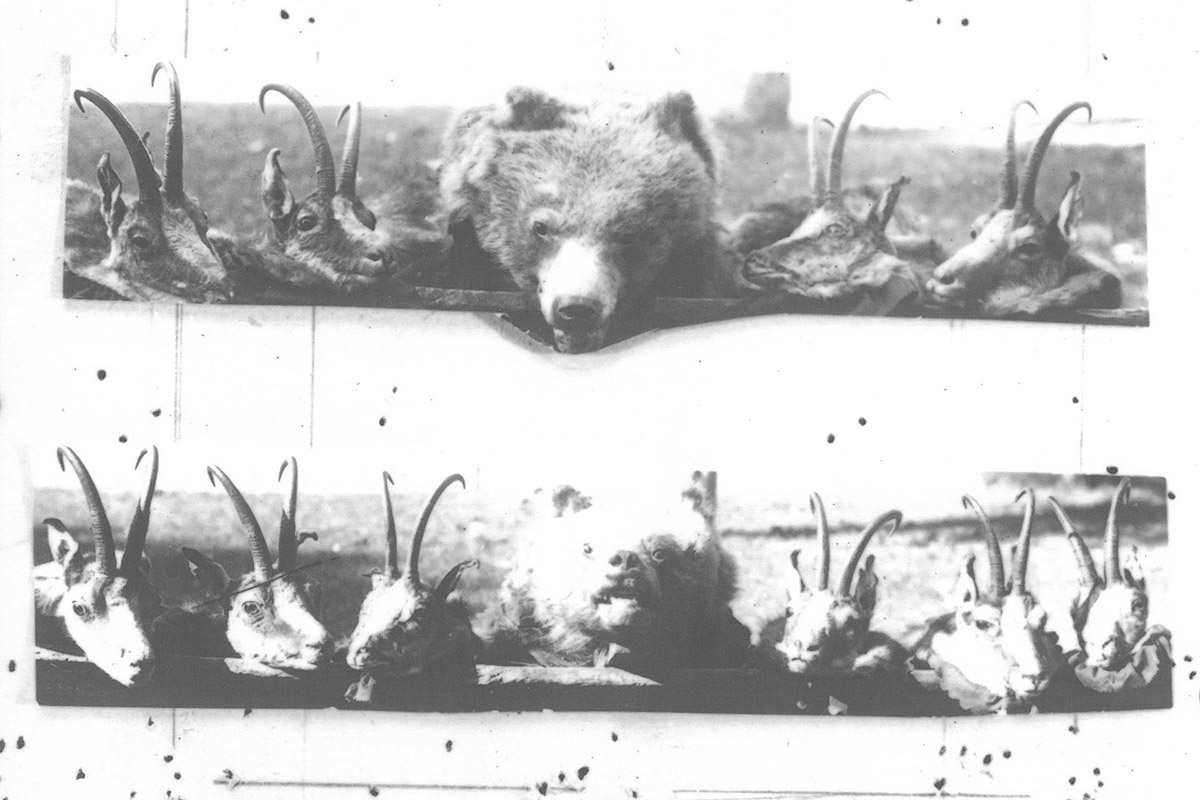

Amedeo di Savoia-Aosta, the Duca delle Puglie e his bear trophy at the end of the hunt of 1921. (© Archivio M.Mancini – Campobasso)

As the 19th century drew to a close, the mountain valleys became increasingly accessible as new roads were opened up, while at the same time there were also major changes in the customs of the time. Hunting was no longer the only leisure activity, but other recreational and sporting activities began to gain ground, including horse riding, tennis and cycling, while hunting also became increasingly popular among the urban middle classes. It was especially during the two periods when the Royal Reserve was closed (1878, 1919), with the accompanying absence of constraints and restrictions, that bear hunting came to resemble a genuine massacre, with the participation of both locals and outsiders. In other words, the bear could once again be freely hunted. It was precisely these events that resulted in the emergence of the first nature conservation movements at both local and national level. Between 1921 and 1922, these finally led to establishment of the Abruzzo National Park. The bear and the chamois became two protected species and, in 1931, the last bear hunt was granted in honour of the king. At the same time, a further change in customs took place… big game hunting disappeared among the main leisure activities and the Apennines became a centre of attraction for winter sports.

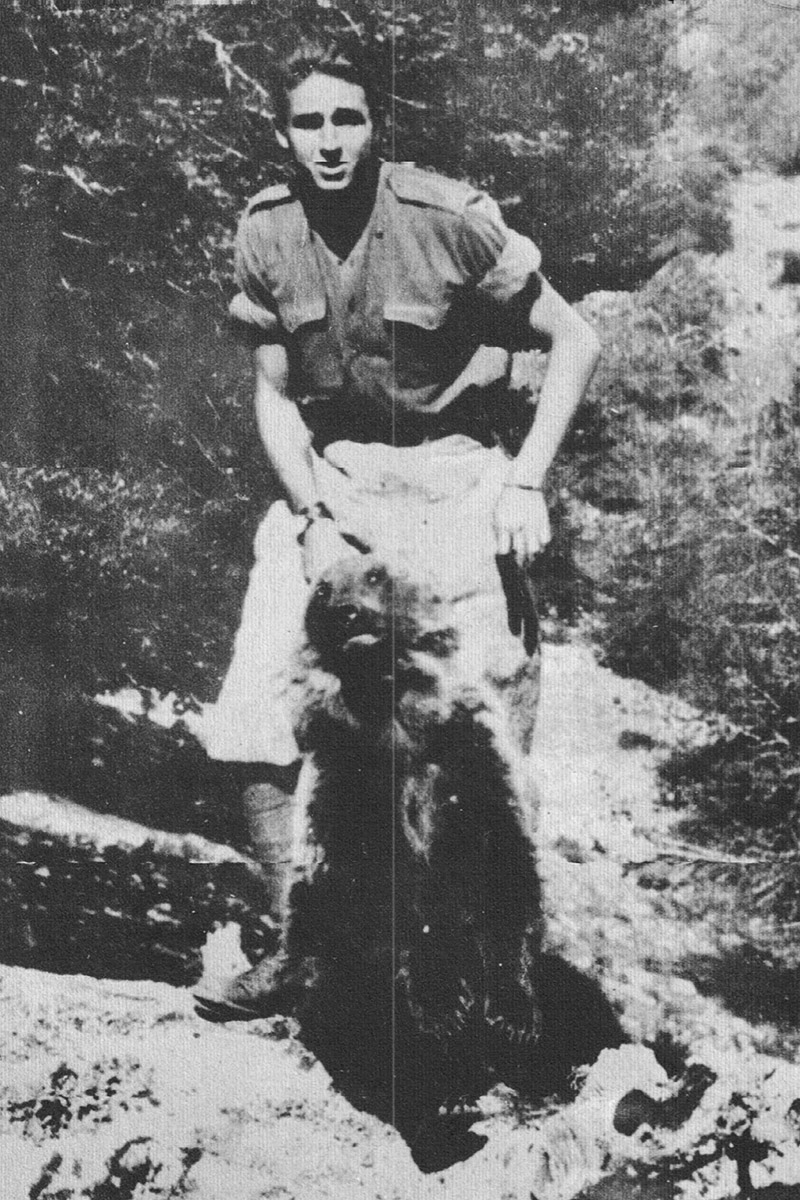

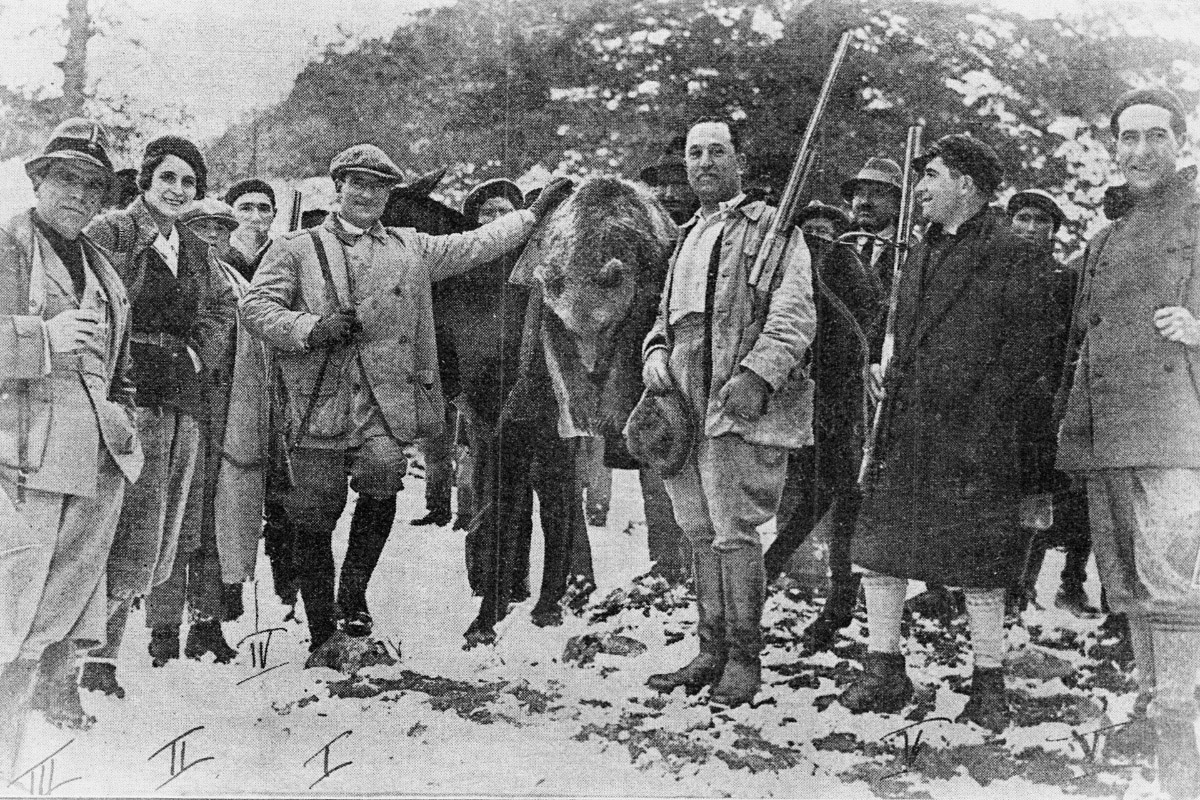

Vintage photo showing some notables and local personages involved in the last official bear hunt in the Abruzzo National Park in 1931. (© Archivio M.Mancini – Campobasso)

With establishment of the Park, the image of the bear underwent a further metamorphosis to become a source of local pride, a tourist attraction and a symbol of the conservation and protection of animals… in other words, of a protected area, today’s Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park. Since the 1970s, the sitting bear has been the Park’s official “my friend the bear” symbol, reinforcing the symbolic familiarity with this animal. In the same years (and particularly over the last decade with emergence of the social media), there has been a growing awareness of the environment and its protection. Bears have increasingly become a public (and consequently also an emotional and political) issue, involving not only protected areas, but also the worlds of research and associations and the public in general.

“My bear friend”, sticker put into circulation by PNALM in the early 1980s, in which the slogan and the Park’s friendly logo contributed to the creation of a brand new image of the plantigrade.

The relationship between the inhabitants of the Apennines and bears has evolved over the centuries. Central to these changes has been the complex and even contradictory relationship with hunting.